Ties Read online

Europa Editions

214 West 29th St., Suite 1003

New York NY 10001

[email protected]

www.europaeditions.com

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to historical events, real people, or real locales are used fictitiously.

Copyright © 2014 by Giulio Einaudi editore s.p.a., Torino

First publication 2016 by Europa Editions

Translation by Jhumpa Lahiri

Original Title: Lacci

Translation copyright © 2016 by Europa Editions

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.

Winner of the Inaugural edition of The Bridge Prize for Best Novel

Cover Art by Emanuele Ragnisco

www.mekkanografici.com

Cover illustration © Jonathan McHugh/Getty

ISBN 9781609453862

Domenico Starnone

TIES

Translated from the Italian

by Jhumpa Lahiri

TIES

INTRODUCTION

By Jhumpa Lahiri

The need to contain and the need to set free: these are the contradictory impulses, the positive and negative charges that interact in Domenico Starnone’s novel, Ties.

To contain, in Italian, is contenere, from the Latin verb continere. It means to hold, but it also means to hold back, repress, limit, control. In English, too, we strive to contain our anger, our amusement, our curiosity.

A container is designed so that something can be placed inside it. It has a double identity in that it is either lacking contents or occupied: either empty or full. Containers often hold what is precious. They house our secrets. They keep us safe but can also imprison, ensnare. Ideally, containers stem chaos: they are supposed to keep things from dispersing, disappearing. Ties is a novel full of containers, both literal and symbolic. In spite of them, things go missing.

The characters in Ties are few: a family of four, a neighbor, a lover who remains offstage. A cat, a carabiniere, a couple of strangers. But there are a number of inanimate objects that also play critical roles in the alchemy of this novel: a swollen envelope that holds a bundle of letters, a hollow cube. Photographs, a dictionary, shoelaces, a home. And what do these objects represent, if not agents of enclosure of various kinds? Envelopes hold letters, and letters contain one’s innermost thoughts. Photos contain time, a home contains a family. A hollow cube can contain whatever we’d like it to. A dictionary contains words. Laces—the literal translation of the Italian title, Lacci—serve to close up our shoes, which in turn contain our feet.

And as these objects are opened one by one—once the elastic around the envelope is removed, once laces are untied—the novel ignites. Like Pandora’s box, each of these objects unleashes acute forms of suffering: frustration, humiliation, yearning, jealousy, envy, rage.

If the myth of Pandora is the leitmotif of Ties, Chinese boxes are the underlying mechanism, the morphology. The entire structure of this novel, in fact, seems to me a series of Chinese boxes, one element of the plot discretely and impeccably nestled within the next. There is no hole in the construction, no fissure. No detail has escaped the author’s attention; like the home of Aldo and Vanda—the husband and wife at the center of this fleet tale—everything is in place, neat as a pin.

In spite of this airtight structure, the effect is exactly the opposite. A volcanic energy erupts, circulates, spills over in these pages. The novel reckons with messy, uncontrollable urges that threaten to break apart what we hold sacred. It is, in fact, about what happens when structures—social, familial, ideological, mental, physical—fall apart. It asks why we go out of our way to create structures if only to resent them, to evade them, to dismantle them in the end. It is about our collective, primordial need for order, and about our horror, just as primordial, of closed spaces.

Chinese boxes are of course an established narrative device to describe a story that is artfully contained within another story: examples include Lampedusa’s short story “The Siren,” Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Ties plays whimsically with this conceit. It is one novel but it is also several. Though the elements are precisely aligned, though they correspond to one another, they are also severed. One can read the novel as three panels of a triptych, but the image of Chinese boxes remains in my opinion more apt, in that it suggests an infinite number of openings and closings, an endless game.

Let’s take it a step further and regard the novel itself as a narrative container. I first called Ties a Pandora’s box, and then a series of Chinese boxes, but it is also a magician’s box that enchants us, from which things appear and disappear. The story jumps around, shifting tonally. And though I have just posited that it is an extremely orderly novel, it is also a gloriously messy one. Points of view are distinct but also blur, time leaps back and forth, expanding and contracting. The trajectory is point to point but also elliptical. The effect is coherent but unpredictable, blissfully free of norms.

Starnone’s genius is his ability to play constantly both inside and outside the box, now conforming to it, now escaping it. It is this double-pronged illusion that gives the novel such equilibrium, such force. Though perfectly plotted, though utterly satisfying, this is a novel without a formal conclusion. We never see the end of it. There are obvious scenes to come, always more boxes to confront. The finale has been truncated and we are left in suspense. Only a writer with dexterity of the highest order is capable of pulling off a trick like this.

The metaphor of the magician’s box leads us to one of the central, recurrent themes in Ties: that of being deceived, betrayed. Whether cheated by an anonymous hustler or an errant husband, by a trick of the mind or fortune’s whims, characters are repeatedly being duped, hoodwinked, fooled, lied to. Adultery, in this novel, implies both a physical and moral transgression: stepping outside the family home, breaking the bond between husband and wife. Although breaking that bond may entail little more than moving from one enclosure to the next.

In spite of all the solid walls, the reassuring structures we seek out and build around us, there is nowhere, Starnone seems to suggest, to feel safe. Life is what betrays the container, what spills out. Cesare Pavese comes to mind; in his short story “Suicidi” (Suicides) he observes, “La vita è tutto un tradimento”—All of life is betrayal. That is to say, time betrays us, people we know and don’t know betray us, we betray ourselves by living, by growing old, and, finally, by dying. Starnone complicates Pavese’s observation—unpacking it, if you will. Ties is less about betrayal than about pain that returns, that resurfaces: in spite of diligent efforts to organize experiences, emotions, memories, they can’t be packaged, hidden, repressed, filed away. Fittingly, at one point, there is a dream in these pages—a fecund, indelible image. For dreams both contain and set free the roiling matter of our psyches.

The multiple themes encased in the novel are densely layered. It is a rumination on old age, on the passage of time, on frailty, on solitude. On forms of inheritance: economic, genetic, emotional. It is a book about marriage, about procreation, about parenting, about love. Love is a key word in Ties, a term that is questioned, redefined, shunned, treasured, maligned. At one point Vanda says that love is merely “a container we stick everything into.” It is, in essence, a hollow vessel, a placeholder that justifies our behaviors and choices. A notion that consoles us, that cons us more often than not.

In spite of its stormy course, its dark vision, Ties points faithfully toward freedom and its corollary, happiness. Be they virtues or privileges, be they considered a crime, freedom and happiness, in this novel, are one and the same: wild states of being that refuse to be domesticated, that cannot be trammeled or curbed. T

ies looks coldly at the price of freedom and happiness. It both celebrates and castigates Dionysian states of ecstasy, of abandon. And though happiness often involves linking ourselves to other people—in other words, stepping outside the confines of ourselves—it is something, in the final analysis, that characters experience privately, alone.

Pandora’s box sets free the evils of the world. Only hope remains. Ties, too, though caustic, though troubling, remains a hopeful novel. It is bathed in light, it contains moments of great tenderness. It is lyrical, agile, energetic. It is also very funny. It is a great work of literature. And nothing gives me more hope than this.

As the translator of Ties into English, I too have had to break open a formidable container: the container of Italian. For many years I have searched within that box, trying to piece together a new sense of myself. My relationship to Italian incubates and evolves in a sacred vessel I hold dear. My impulse has been to guard it, to not contaminate it.

Then I read Ties when it was published in Italy, in the autumn of 2014, and fell in love with it. I had not yet translated anything from Italian to English. In fact, I was resistant to the idea. I was immersed in Italian, in a joyous state of self-exile from the language (English) and the country (the United States) that have marked me most significantly. But the impact of this novel overwhelmed me and my desire, as soon as I read it, was to translate it someday.

I identified strongly with Aldo because, like him, I had run away, in my case to Italy, taking refuge in the Italian language in search of freedom and happiness. I found them there. Then, like Aldo, after some euphoric years away, with certain misgivings, I decided to return. I moved back to the city that had once been home, where I was surrounded by the language I had deliberately stepped away from. I did all this with a broken heart.

The month after I returned to the United States, Ties won the Bridge Prize for fiction, awarded each year to a contemporary Italian novel or story collection that will be translated into English, and to an American work of fiction that will be translated into Italian. I read the novel for a second time, even more moved by it, and then I discussed it with the author at a panel at the Italian Embassy in Washington, D.C. Following the event, Starnone asked if I would consider translating it. I said yes. As a result, this novel has accompanied me during a particularly challenging year of my life. Incidentally, much of it was translated as I was packing up my home, putting everything I have accumulated in my life into a series of boxes.

As a translator I remain outside the container, in that the novel remains the brainchild of a fellow writer. It is liberating in that I don’t have to fabricate anything. But I am bound to a preexisting text, and thus aware of a greater sense of responsibility. There is nothing to invent but everything to get right. There is the challenge of transplanting into a different language what already thrives, beautifully, in another. In order to translate Ties I had to purposefully distance myself from Italian, the language I have come to love most, dismantling it, rendering it invisible.

In Starnone’s novel, life has to be reread in order to be fully experienced. Only when things are reread, reexamined, revisited, are they understood: letters, photos, words in dictionaries. Translation, too, is a processing of going back over things again and again, of scavenging and intuiting the meaning, in this case multivalent, of a text. The more I read this novel, the more I discovered.

I was struck, as I translated, by a fertile lexicon of terms that mean or describe a state of disorder. I made a list of them: a soqquadro, devastazione, caos, disordine. Sfasciato, squinternato, divelto, sfregiato. Scempio, disastro, buttare per aria. These terms are stemmed by a single, prevailing, recurrent word: ordine. Order. Or perhaps it is order that is constantly under threat, the terms for disaster engulfing it, undermining it.

Another word that stood out to me, that is used frequently, is scontento. It can mean unhappiness in English, but it is far stronger than that. It is an amalgam of frustration, dissatisfaction, disappointment, discontent. And though the roots are different, I couldn’t help but ponder the proximity, the interplay between certain verbs in the Italian that sound or look similar, that are thematically linked: contenere (to contain) and contentare (to make happy). Allacciare (to lace, tie down) and lasciare (to leave).

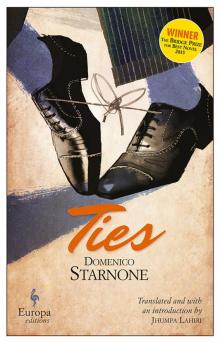

As I’ve already noted, the title of this novel, in Italian, is Lacci, which means shoelaces. We see them on the cover, thanks to an illustration chosen by the author himself. A person, presumably a man, wears a pair of shoes whose laces are tied together. It is a knot that will surely trip him up, that will get him nowhere. We don’t see the expression on the man’s face, in fact we see very little of his body. And yet we fear for him, feel a little sorry for him, perhaps laugh at him, given that he already seems to be in the act of falling on his face.

But lacci in Italian are also a means of bridling, of capturing something. They connote both an amorous link and a restraining device. “Ties” in English straddles these plural meanings. “Laces” would not have. Having made this choice, I am struck by the relationship in English, too, between untie and unite, two opposing actions counterpoised in this novel.

What happens when laces are untied? Indeed, as I have already argued, the entire novel is a series of tying and untying, of putting in order and pulling apart, of creating and destroying. “Writing is more about destroying than creating,” Karl Ove Knausgård has observed. There is some truth to this. But art is nothing if not contained by a unique structure, held in place by an inviolable unique form.

My American friend and fellow translator from Italian, Michael Moore, believes that Starnone—a Neapolitan writer who grew up speaking dialect, who learned to write in Italian, as so many Italian writers do—is one of the few contemporary Italian authors today who writes in an uncontaminated Italian. My Italian writer friends, too, hail his transparent, nuanced, erudite prose. I agree with them. Its rhythm, its lexicon floats free from any trend. His style is protean. His sentences can be lapidary but others are intricate, centripital, revealing a subtle inlay of clauses—Chinese boxes on the syntactical level. In translating them I have often had to rupture their design, restructuring in order to render them at home in English. His prose is steeped in classical allusions, psychoanalytic references, the laws of physics.

This novel, his thirteenth work of fiction, fits into no distinct category or genre: it is a clever whodunit, a comedy of errors, a domestic drama, a tragedy. It is an astute commentary on the sexual revolution, on women’s liberation, on rational and irrational urges. It is like a cube, perfectly proportioned; turn it around, and you will discover another facet.

There is a passage in this novel that stopped me in my tracks the first time I encountered it, that moves me in particular each time I reread it. It involves a writer alone in his study, not writing but, rather, sorting through his books and papers. It is a meditation on existence and on identity in its most essential form, and it helps me to understand the impetus behind what I myself do. It is a passage about leaving traces, about trying desperately, in vain, to tie ourselves to life itself. It lays bare the flawed human impulse to endure.

Writing is a way to salvage life, to give it form and meaning. It exposes what we have hidden, unearths what we have neglected, misremembered, denied. It is a method of capturing, of pinning down, but it is also a form of truth, of liberation.

If one is to unpack all the boxes, this is a novel, I believe, about language, about storytelling and its discontents. The disquieting message of Ties is not so much that life is fleeting, that we are alone in this world, that we hurt one another, that we grow old and forget, but that none of this can be captured, not even by means of literature. Containers may be the destiny of many in that they hold our remains after death. But this novel reminds us that narrative refuses to stay put, and that the effort of telling stories only pins things down so far. In the end it is language itself that is the most problematic container; it holds too much and

too little at the same time.

I am deeply grateful to Domenico Starnone not only for the work he has produced but for inviting me and trusting me to translate it. It is with Lacci that I return to English after a hiatus of not working with the language for nearly four years. It is this project that has inspired me to reopen my English dictionaries, my old thesaurus, after a considerable period of neglect. My fear, before I began, was that it would distance me from Italian, but the effect has been quite the contrary. If anything I feel more tied to it than ever. I have encountered countless new words, new idioms, new ways of phrasing things. And though I translated the book in America it has also brought me closer in some sense to Rome, the city in which I was living when I discovered the book, the city in which much of the novel’s action is set. It is in Rome, the city to which I will forever happily return, that I revised and completed the translation, and where I write these words of introduction.

These scattered observations cannot possibly contain my admiration for what Domenico Starnone has achieved in these pages. I am tempted to better organize my thoughts, but all I really want to say is: open this book. Read it, reread it. Discover the words, the voice, the sleight of hand of this brilliant writer.

BOOK ONE

CHAPTER ONE

1.

In case it’s slipped your mind, Dear Sir, let me remind you: I am your wife. I know that this once pleased you and that now, suddenly, it chafes. I know you pretend that I don’t exist, and that I never existed, because you don’t want to look bad in front of the highbrow people you frequent. I know that leading an orderly life, having to come home in time for dinner, sleeping with me instead of with whomever you want, makes you feel like an idiot. I know you’re ashamed to say: look, I was married on October 11th, 1962, at twenty-two; I said “I do” in front of the priest in a church in the Stella neighborhood, and I did it for love, nothing forced me into it; look, I have certain responsibilities, and if you people don’t know what it means to have responsibilities you’re petty. I know, believe me, I know. But whether you like it or not, the fact remains: I am your wife and you are my husband. We’ve been married for twelve years—twelve years in October—and we have two children: Sandro, born in 1965, and Anna, born in 1969. Do I need to show you their birth certificates to shake some sense into you?

Ties

Ties