- Home

- Domenico Starnone

Ties Page 2

Ties Read online

Page 2

Enough, sorry, I’m going overboard. I know you, I know you’re a decent person. But please, as soon as you read this letter, come home. Or, if you still aren’t up to it, write to me and explain what you’re going through. I’ll try to understand, I promise. It’s already clear to me that you need more freedom, as it should be, so the children and I will try to burden you as little as possible. But you need to tell me word for word what’s going on between you and this girl. It’s been six days and you haven’t called, you don’t write, you don’t turn up. Sandro asks me about you, Anna doesn’t want to wash her hair because she says you’re the only one who can dry it properly. It’s not enough to swear that this woman, or girl, doesn’t interest you, that you won’t see her again, that she doesn’t matter, that it was just the result of a crisis that’s been building inside you for a while. Tell me how old she is, what her name is, if she works, if she studies, if she does nothing. I bet she was the one who kissed you first. I know you’re incapable of making the first move, either they reel you in or you don’t budge. And now you’re stunned, I saw the look on your face when you told me: “I’ve been with another woman.” Do you want to know what I think? I think you have yet to realize what you’ve done to me. It’s as if you’ve stuck your hand down my throat and pulled, pulled, pulled to the point of ripping my heart out, don’t you get it?

2.

Reading over what you write, I come off as the torturer and you the victim. I won’t stand for this. I’m trying my best, I’m going to lengths you can’t possibly imagine, and meanwhile you’re the victim? Why? Because I raised my voice a bit, because I shattered the water carafe? You have to admit, I had my reasons. You turned up without warning after almost a month’s absence. You seemed calm, even affectionate. I thought, thank god, he’s back to himself again. Instead you told me, as if it were nothing, that the same person who, four weeks ago, didn’t matter—to your credit, deciding it was time to give her a name, you called her Lidia—is now so important that you can’t bear to live without her. Setting aside the moment in which you acknowledged her existence, you spoke to me as if it were a public service announcement and that all I’d have to say was: okay, thanks, go off with this Lidia, I’ll do my best to not bother you anymore. And as soon as I tried to react you stopped me, you went on to talk in abstract terms about the family: the family in history, the family in the world, your family of origin, ours. Was I supposed to shut up and be nice? Was that what you expected? You’re ridiculous at times. You think it’s enough to toss together general topics and some anecdote of yours to square things away. But I’m sick of your little games. You told me for the umpteenth time, in a pathetic tone you seldom use, how your parents’ miserable marriage ruined your childhood. You used a dramatic image: you said that your father had wrapped barbed wire around your mother, and that every time you saw a sharp clump of iron pierce her flesh you suffered.

Then you moved on to us. You explained that just as your father had damaged all of you, so you—since the ghost of that unhappy man who made you all unhappy still torments you—were afraid of damaging Sandro, Anna and, most of all, me. See how I didn’t miss a word of it? For a long time you reasoned with pedantic calm about the roles we were imprisoned in by getting married—husband, wife, mother, father, children—and you described us—me, you, our children—as gears in a senseless machine, bound always to repeat the same foolish moves. And so you carried on citing a book now and then to shut me up. At first I thought you were talking like that because something so terrible had happened to you that you no longer remembered who I was: a person with thoughts, feelings, a voice of her own, and not a puppet in your Pulcinello show. It dawned on me somewhat late that you were trying to be helpful. You wanted to make me realize that, by destroying the life we shared, you were in fact freeing me and the children, and that we should be grateful for your generosity. Oh, thank you, how kind of you. And you were offended because I threw you out of the house?

Aldo, please, think it over. We need to face one another, seriously; I need to understand what’s happening to you. In our many years of living together you were always an affectionate man, both with me and the children. You’re nothing like your father, I assure you, and all that stuff you said about the barbed wire, about the gears and other nonsense never occurred to me. Instead it’s occurred to me—and this is true—that in recent years something about us has been changing, that you’ve been looking with interest at other women. I vividly remember the one at the campground, two summers ago. You were lying in the shade, reading for hours. You were busy, you said, and so you weren’t paying attention to me or the children, you were studying under the pine trees or stretched out on the sand, writing. But when you looked up it was to look at her. And your mouth hung open a little, the way it does when you have a confusing thought in your head that you’re trying to figure out.

At the time I told myself that you were doing nothing wrong: the girl was lovely, we can’t control our eyes, sooner or later a glance slips out. But I suffered, acutely, especially when you started offering to do the dishes, something that never happened. You darted off toward the sinks as soon as she set out and returned when she came back. Do you think I’m blind, insensitive, that I didn’t notice? I told myself: calm down, it doesn’t mean anything. It seemed inconceivable to me that another woman might appeal to you, because I was convinced that if you were attracted to me once you’d be attracted to me forever. I believed real feelings never changed, especially in marriage. It happens, I told myself, but only to superficial people, and he isn’t one. Then I told myself that it was an era of change; even you theorized that we needed to shake things up, that maybe I was too caught up in household chores, in managing our money, in the children’s needs.

I started looking at myself secretly in the mirror. How was I, what was I? Two pregnancies had barely altered me, I was an efficient wife and mother. But evidently being almost identical to the time we’d met and fallen in love wasn’t enough, to the contrary—maybe that was the mistake; what I had to do was reinvent myself, be more than just a good wife and mother. So I tried to look like the one at the camp, and like the girls that no doubt hovered around you in Rome, and I made an effort to participate more in your life outside the house. And a different phase began, slowly. I hope you noticed. Or no? You noticed but it didn’t help? Why not? Didn’t I do enough? Was I stuck midstream, unable to match up to the other women, always being who I was? Or did I go overboard? Did I change too much, did my transformation upset you? Were you ashamed of me, did you not recognize me anymore?

Let’s talk about it, you can’t leave me in the lurch. I need to know about this Lidia. Does she have her own place, do you sleep there? Does she have what you were looking for, what I no longer have, or never did? You snuck off, avoiding speaking to me clearly at all costs. Where are you? The address you left is in Rome, so is the phone number, but you don’t respond when I write, the phone keeps ringing. What do I have to do to find you? Call one of your friends, come to the university? Start screaming in front of your colleagues and students? Do I have to let everyone know how irresponsible you are?

I have to pay the gas and the electricity. There’s the rent. And two kids. Come back right away. They have the right to parents who take care of them day and night, a father and mother to have breakfast with in the mornings, who take them to school and pick them up again at the gates. They have the right to have a family, a family with a house where you eat lunch together and play and do homework and watch a little television and then have dinner and then watch some more television and then say goodnight. Say goodnight to Dad, Sandro, and you too, Anna, say goodnight to your father without whining, please. No fairy tale tonight, it’s late; if you want a fairy tale then hurry up and brush your teeth, Dad will tell you one, but not more than fifteen minutes, then to bed, otherwise tomorrow you’ll be late for school, besides your father has an early train to catch, if he shows up late they’ll scold him. And th

e kids—do you no longer remember?—they run to brush their teeth, then come to you for the fairy tale, every night, the way it’s been since they were born, the way it should be until they grow up, until they go off, and we grow old. But maybe you’re no longer interested in growing old with me or even in watching your children grow up. Is that it? Is it?

I’m afraid. The house is isolated, you know how it is in Naples, it’s a scary place. At night I hear noises, laughter, I don’t sleep, I’m worn out. What if a thief gets in through the window? What if they steal the television, the record player? What if someone who’s angry with you kills us in our sleep for revenge? Is it possible that you don’t realize the weight you’ve dumped on top of me? Have you forgotten that I don’t have a job, that I don’t know how to get by? Don’t make me lose my patience, Aldo, be careful. If I start to lose it, I’ll make you pay.

3.

I saw Lidia. She’s very young, beautiful, well-bred. She listened carefully to what I had to say about you. And she said something quite reasonable: you need to talk to him, I have nothing to do with your relationship. Indeed, she’s a stranger, it was wrong of me to look for her. What could she have told me? That you fell for her, that you’re taken by her, that you liked her, that you still like her? No, you’re the only one who can explain every angle of this to me. She’s nineteen. What does she know, understand? You’re thirty-four, a married man, well-educated, you have a respectable job, you’re highly regarded. It’s up to you to give me a solid explanation, not Lidia. And yet all that you’ve told me, in two months, is that you can’t live with us anymore. Right? And what’s the reason? With me—you’ve sworn—there wasn’t a problem. As for the children there was no arguing, they’re your children. They get along well with you and you, by your own admission, with them. Well then? No reply. All you do is babble: I don’t know, it happened. And when I ask if you have a new place, new books, your own things, you say no, I don’t have anything, I’m a mess. And when I tell you, you live with Lidia, you sleep together, you eat together, you shrug it off, you mumble, no, of course not, we’re seeing each other, that’s all. I’d like to warn you, Aldo. Don’t keep doing this, I can’t take it. Each of our conversations rings false to me. Actually, I’d say that I’m making a concerted effort that’s destroying me while you keep lying, and by lying you make clear that you no longer have any respect for me, that you’re rejecting me.

I’m getting more scared. I’m scared that you’ll contrive to transmit the spite you harbor toward me to the children, to our friends, to everyone. You want to isolate me, cut me out completely. And, what matters most, you want to avoid every attempt to reexamine our relationship. This is driving me crazy. I, unlike you, need to know; it’s crucial that you tell me, point by point, why you’ve left. If you still consider me a human being and not an animal to ward off with a stick, you owe me an explanation, and it had better be a decent one.

4.

I get it now. You decided to pull out, abandoning us to our fate. You want your own life, there’s no room for us. You want to go wherever you like, see whomever you wish, become the person you’d like to be. You long to leave our little world behind and join the great wide one with a new woman. In your view, we’re proof of how you wasted your youth. You think of us as an illness that’s kept you from growing, and without us you hope to make up for it.

If I’ve understood properly, you disapprove of my saying us so often. But that’s how it is: the kids and I are us, and you, by now, are you. By walking away you’ve destroyed our life with you. You’ve destroyed how we once saw you, what we believed you were. You did so knowingly, planning it out, forcing us to realize that you were just a figment of our imagination. And now here were are: Sandro, Anna and I, subject to poverty, to an absolute lack of security, to despair, while you enjoy yourself, god knows where, with your lover. My children, as a result, are now mine alone; they don’t belong to you. You’ve seen to it that their father has become an illusion to them, and to me.

Nevertheless you say you want to maintain a relationship. Fine, I don’t object, the key is that you explain how. You want to be a father in every respect, even though you’ve shut me out of your life? You want to take care of Sandro and Anna, devote yourself to them without me? You want to be a shadow that materializes once in a while, and then you want to leave them to me? Ask the kids, see if it’s OK with them. All I can say is that you’ve suddenly snatched away what they thought was theirs, and that this causes them a great deal of pain. Sandro thought of you as the center of his world and now he’s flailing. Anna doesn’t know what she’s done wrong but she thinks that whatever it is it must be so serious that you’ve punished her by leaving. Welcome to the situation. I’ll keep watch. But I’m telling you straight off that, first, I will not let you ruin my relationship with them and, second, I will prevent you from hurting my children any more than you already have by proving yourself to be a father who is utterly false.

5.

I hope it’s clear to you now why the end of our relationship also entails the end of your relationship with Sandro and Anna. It’s easy to say: I’m the father and I want to keep being one. In practice you’ve demonstrated that there’s no room for the children in your current life, that you want to free yourself of them as you freed yourself of me. When, exactly, were you truly concerned for them?

Here’s the latest, assuming that it interests you. We’ve moved. I couldn’t make the rent with the money I had. We went to live with Gianna, making do. The kids had to change schools and make new friends. Anna suffers because she can’t see Marisa anymore, and you know how much that meant to her. It was clear to you from the start that things would end up this way, that by leaving me you would subject them to all manner of discomfort and humiliation. But have you ever done a thing to avoid this? No, you’ve only thought of yourself.

You’d promised Sandro and Anna that you would spend the summer with them, the whole summer. You came half-heartedly one Sunday to get them, they were happy. But how did that end up? You brought them back to me after four days saying that looking after them put you on edge, that you didn’t feel up to the task, and then you left with Lidia, not showing up again until the fall. You didn’t bother yourself with what vacations they would have taken, where, how, with whom, with what money. Your needs were what counted, not those of your children.

But let’s move on to the Sunday visits. You arrived late on purpose, you only stayed a few hours. You never took them out, you never played with them. You watched TV, and they were seated there beside you, expectant, watching you.

And the holidays? At Christmas, on New Year’s, on the Epiphany, for Easter, you never got in touch. On the contrary, when the kids asked you explicitly to take them with you, you kept saying that you didn’t have a place to put them, as if they were strangers. Anna drew you a picture of one of her ominous dreams and described it to you in detail. But you didn’t blink, you weren’t moved, you just sat there telling her, what pretty colors. You only perked up when, in the course of our discussions, you felt the need to highlight that you had your own life: that your life wasn’t our life, and that the separation was final.

I know now that you’re afraid. You fear that the children weaken your resolve to cut us out, that they get in the way of your new relationship, that they ruin it. Therefore, my dear, when you say you still want to be a father, it’s just talk. The reality is something else: in freeing yourself of me, you also want to free yourself from your children. It’s obvious that your critique of the family, of traditional roles and other drivel, is just an excuse. You’re hardly fighting against an oppressive institution that reduces people to their assigned roles. If this were the case you’d realize that I agree with you, that I, too, want to free myself and change. If this were the case, once you’d dismantled the family, you’d pause at the edge of the emotional, economic and social cliff you’re tossing us over and you would hasten to recognize our feelings, our des

ires. But no. You want to rid yourself of Sandro, Anna and me as people. You see us as an obstacle to your happiness, a trap that smothers your desire for pleasure. You consider us an irrational, malign residue. You’ve said it to yourself from the very beginning: I need to get a grip on myself, even if it kills them.

6.

You raise the example of the staircase. You say, you know when we go up the stairs? One foot after the other the way we learned when we were kids. But the joy of taking those first steps has disappeared. Growing up, we were molded by the strides of our parents, our older siblings, the people we’re tied to. Now our legs move according to acquired habits. And the tension, the emotion, the happiness of each step must have perished along with the uniqueness of our stride. We proceed believing that the movement of our legs is our own, but it isn’t so; there’s a small crowd that’s shaped us, moving up those steps with us, and the steadiness of our legs simply stems from conformity. Either we change our step—you conclude—rediscovering the joys of starting out, or we condemn ourselves to the dread of normality.

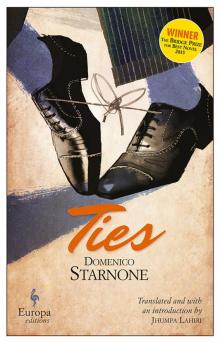

Ties

Ties